Static and Dynamic Linking

If you look up "static vs dynamic linking" you'll get lots of articles and videos that all explain it like this:

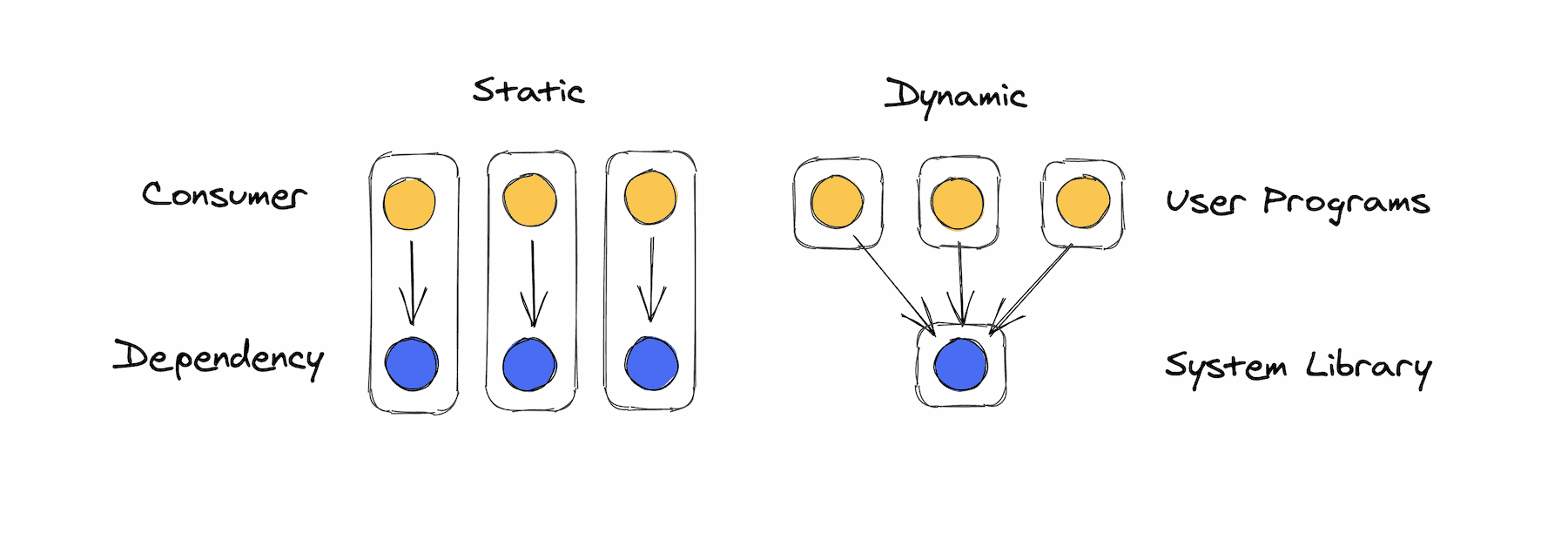

Lots of programs need to access the same system libraries and there's two ways to do it. One solution is static linking, where each program gets its own copy of the library included in its executable at compile-time. The alternative is dynamic linking, where one copy of the system library is shared between each program and they call it at runtime, facilitiated by the operating system.

As always, neither approach is "better," they each have tradeoffs. Static linking is simpler, and the communication between program code and library code is typically faster. If there's a problem using the library, you'll catch it at build-time and it'll be easier to debug. You know exactly what code will be running in your executable ahead of time. Dynamic linking, on the other hand, uses less disk and memory since only one copy of the library is needed. Additionally, every program can use the most up-to-date version of the library without having to recompile. If an update patches a security vulnerability, you get that patch automatically. But if an update introduces a vulnerability, you also get that automatically.

This is the same way I (and I'm guessing many others) learned about it in an operating systems class. For a while, it didn't seem like an especially relevant concept for me. I'm not working on low level code where this specific problem comes up. Over time, though, I've realized that if you zoom out of the narrow definition, this is a much more profound concept that's relevant at every layer of the stack. All throughout software systems you have to deal with shared dependencies, and you always have a choice between some version of static and dynamic linking. The same tradeoffs exist every time, and evaluating these tradeoffs can help you make the appropriate choice for the given context.

At its core, static vs dynamic linking is about where to draw boundaries. Do you combine the consumer and dependency into one unit, or do you separate them? Every situation with shared dependencies poses the same question.

Common Web Libraries

It used to be common for websites to use an external CDN to include dependencies like jQuery. If another website needs the same dependency and uses the same CDN, it can use the browser's cached version, effectively sharing the dependency. Today, it's common for web apps to have all their dependencies bundled into them statically. As you navigate the web, you're probably downloading React over and over again.

Dynamic linking can improve network and memory usage, but it increases the room for errors and can make them harder to debug and fix. It also has security implications — many large companies don't use 3rd party CDNs because they want full control over the code they distribute.

Edit: As of version 85, Chrome partitions its cache by URL, meaning resources aren't shared across websites.

Sharing Across Microfrontends

It's common for large web applications to be split up into multiple smaller apps. PayPal.com consists of several separate web applications developed by separate teams, all of which share dependencies. For example, many of them need to display the same header. It could be consumed at build-time as an npm module, but coordinating header updates across teams would be prohibitively difficult.

For dependencies like React, it doesn't affect the user experience very much if different apps are using different versions. Different headers on different pages, though, would be jarring and unacceptable. Because of this, each app fetches the header dynamically and bundles React statically. As technologies like Webpack Federation mature, it may become more common to dynamically link more dependencies and reap the performance benefits of smaller bundle sizes.

Microservices

One way to build a complex backend system is as one big application, bundling the parts together statically at build-time. Or, you can separate the parts into services that communicate over HTTP dynamically at runtime. Static linking is much simpler — having to communicate over the network and deploy separately introduces lots of new failure modes. It can be harder to develop and test locally and to debug problems, and communication between parts is much slower. On the other hand, separated services can scale independently and be more resource efficient. Decomposing the system into small pieces with clearly defined boundaries can also make it easier to manage each piece, especially at a big company where each piece has a full team dedicated to it.

Compute Platforms

Let's say you're building a function-as-a-service platform. Customers will give you JavaScript functions and you're responsible for running them. Those functions depend on a JavaScript runtime. You can package a copy of Node with each function using containers or something similar. Or you can run a JavaScript engine yourself, and share it between multiple customers' functions, like Cloudflare Workers does. Cloudflare uses dynamic linking here primarily because of resource constraints. AWS doesn't use a language VM for Lambda in part because of security tradeoffs.

This can extend to any compute platform that runs multiple tenants. Another dependency is the operating system. You can give each tenant its own operating system using VMs, or you can share one kernel between multiple tenants using containers. Even further down, every tenant has a dependency on an actual server. You can give each tenant its own machine, or share one machine between multiple tenants using VMs.

Conclusion

As you've hopefully been convinced of by now, static vs dynamic linking is a universal pattern that applies to any situation with shared dependencies — i.e. everywhere in software systems. In each instance of the problem, the basic set of tradeoffs are the same, and the same questions should be asked. How much more resource efficient is dynamic linking and how important is that? How much more difficult will it be to debug problems if we separate out the dependency? How will the performance of using the dependency be impacted? Do we need every consumer to always use the latest version? Are there important security tradeoffs?